How long do you need to use opioids after knee replacement surgery is a common question? Do you need to get back to work and wonder how long before you can drive? Opioid use and driving do not go together. If an accident occurs and you are still taking opioids it could land you in serious legal trouble.

How long do you need to use opioids after knee replacement surgery is a common question? Do you need to get back to work and wonder how long before you can drive? Opioid use and driving do not go together. If an accident occurs and you are still taking opioids it could land you in serious legal trouble.

Many people also worry about opioid addiction following surgery, since they have read or heard about the increasing rates of addiction to prescription pain medications.

Maybe you are just interested in finding out how long the most intense pain lasts and what the typical pain management protocol is like.

The well researched answer is, less than 10% of people who don’t use opioids before surgery are still taking them at 6 months, but that data doesn’t really answer questions about going back to work and driving which you will need to start doing much sooner especially if you are pre-retirement.

How to Effectively Use Opioids After Knee Replacement

My advice, which I offer in more detail in my book, is simply this. The first two weeks you will experience a great deal of chemical pain, which is related to the molecules that rush into the area in an acute injury; and bone pain, pain that is caused by cutting the ends of the long bones. Most people in order to feel comfortable will need some type of opioid during this time to get them through. Opioids have some well known side effects like nausea in limited cases, constipation quite frequently and well let’s just call it brain fog.

Constipation can usually be managed effectively with a preemptive strategy, taking in plenty of water, taking over the counter prescriptions for constipation before you get constipated and paying attention to the types of food you eat. Consuming lots of cheese and meat, which are tough to digest, will exacerbate the problem.

I recommend taking the opioids after knee replacement during this two week time period at the prescribed levels on a time managed program (meaning take them every __ hours even before you start to experience pain) and work your tail off on your range of motion, the hardest task to complete following a knee replacement.

Since you need to be on the pain medicine secondary to the chemical and bone pain, use it to your advantage and knock out the hardest task out right at the start. Most of my patients can get off of narcotics after the week two if they follow the program and transition to over the counter medications allowing them to drive and return to work sooner than average.

The Biggest Mistake With Pain Managment

The biggest mistake most people make is not utilizing the opioids to their fullest extent early when they are really needed, focusing on restoring range of motion first and foremost. If the range task lingers, so will the opioid use, they go together hand in glove.

The biggest mistake most people make is not utilizing the opioids to their fullest extent early when they are really needed, focusing on restoring range of motion first and foremost. If the range task lingers, so will the opioid use, they go together hand in glove.

If you’ve restored your range of motion and are slowly progressed your strength exercises you should not have a great deal of pain going forward.

The longer one takes an opioid prescription, the more difficult it will be to get off opioids after knee replacement surgery, which leads into this next section about the consequences of using a lot of opioid pain medication prior to surgery.

Opioid Use Before Surgery Leads to Longer Use After Surgery

Only 8.2% of opioid naïve patients (those who had not used opioids prior to surgery) were using opioids at 6 months, while 53.3% of knee replacement patients who reported opioid use the day of surgery continued to use opioids after knee replacement at 6 months.

The strongest predictor of long-term opioid use was taking high-dose opioids before surgery or anything greater than 60 mg of oral morphine a day.

Calculate Your Risk

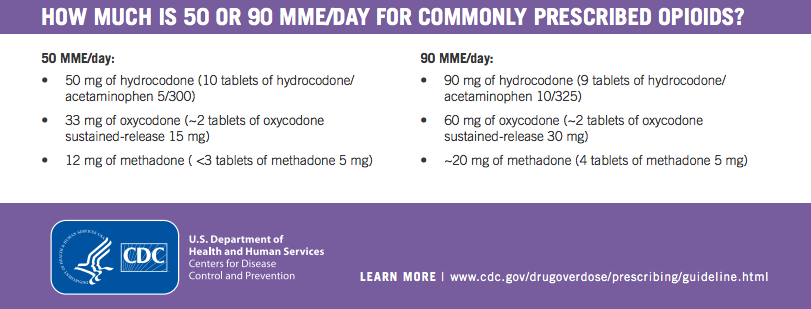

You can calculate your morphine milligram equivalent MME using this handy conversion graphic put out by the CDC which shows you how to convert other prescription pain medicines into an equivalent morphine dose so you can determine how close you are to this important threshold.

Those patients taking >60 mg oral morphine equivalents preoperatively had an 80% likelihood of being on opioids after knee replacement at 6 months postoperatively.

Those patients taking >60 mg oral morphine equivalents preoperatively had an 80% likelihood of being on opioids after knee replacement at 6 months postoperatively.

Other preoperative characteristics associated with persistent opioid use at 6 months were worse pain and functioning, which seems logical, symptoms of depression, and greater catastrophizing (exaggerated responses and worries about pain). [7]

Researchers have theorized that continued opioids after knee replacement surgery could be related to other new pain that has emerged, overall body pain, and dependence, self-medicating for emotional distress and hyperalgesia. Remember that term, hyperalgesia because we are going to get back to it later in the article.

Pre-operative Opioid Use and Poor Outcomes

The bad news is that the inability to get off opioids after knee replacement surgery isn’t even the worse outcome of pre-operative opioid use.

Studies have illustrated that chronic preoperative use is associated with worse self-reported outcomes, longer hospitalizations, increased stiffness, higher rates of complications and failures, and higher risk of in-hospital morbidity and mortality following knee replacement surgery. [1-7]

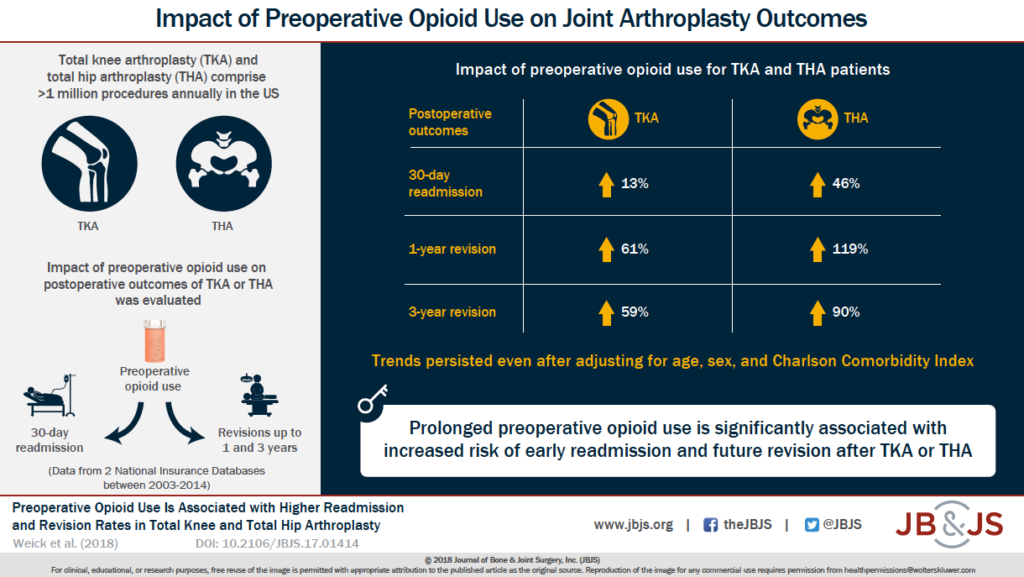

The most recent large-scale study (2018) showed that revision rates and thirty-day re-admission rates were also higher. Researchers concluded that at one year, patients who had been on pre-operative opioid medication for greater than 60 days had 61% and 59% higher odds of revision at one year and 3 years respectively.

The poor outcomes associated with prior opioid use is not limited to knee replacement surgery but includes other varied procedures including bariatric surgery, trauma recovery, kidney transplants and anterior cervical arthrodesis surgery.

So the facts are in, pre-surgical opioid use really throws a wrench in a smooth and successful knee replacement surgery.

Take Home Points

- If at all possible, do not start on the opioid prescription route prior to your surgery.

Then what can I do?

Interestingly whole body pain and depression are associated with low-grade body inflammation as the common precursor of all three; diffuse body pain, joint destruction and pain and depression.

Try to make some diet and lifestyle changes like implementing a whole food diet, lowering stress levels and supporting detoxification pathways. These are possible avenues of relief BEFORE resorting to opioid pain medications.

This is true especially if you have pain in both knees and no history of traumatic joint injury because a systemic problem like low-grade inflammation would indiscriminately target both knees. Known issues with biomarkers for inflammation like C-reactive protein and interleukin would be another clue that whole body inflammation could be an issue.

- Attempt to taper off opioids prior to surgery to ensure a more successful outcome.

This is of course easier said than done and may require you to get support and assistance but it would be better to face the music before surgery so that you don’t multiply your trouble during knee replacement recovery by having to suffer though a infection in the knee or an early revision both of which could have devastating consequences for the long term function of that knee.

Talk to your primary physician or your orthopedic to create a plan. You should never just stop your opioid prescriptions suddenly as this can lead to dangerous side effects.

The Problem of Paradoxical Pain

A little known phenomenon of chronic opioid use is something called hyperalgesia, which means an increase in pain. This is a paradoxical effect. The remedy that is supposed to reduce pain is actually increasing it. Paradoxical effects can occur with other medications like those taken for depression. At times the very same medication that help some, will cause suicide or violence in others. There is still much we do not know about the effects of medications.

A study in 2015 reported that, “although the effect of opioid tolerance and dependence has gained considerable attention, the problem of opioid-induced hyperalgesia—characterized by a paradoxical increase in pain sensitivity—is a less recognized consequence of opioid use.” [9] In fact, it is little known and little studied.

Bob’s Story

I am going to finish by telling you a story of a friend of mine. Let’s call him Bob. He injured his shoulder doing construction and ended up having three different surgeries on that arm over the course of 10 years. He experienced a growing reliance on opioids for pain relief and yet still had 7-8 out of 10 pain in his shoulder.

During that period, he also gained 30 pounds, experienced increase difficulty with his COPD requiring new medications, he become diabetic and was placed on Metformin, was started on another controlled substance, Lyrica for pain relief and experiencing swelling in his leg for which he took a water pill.

After a snafu with his insurance resulting from a cross country move and loss of paperwork he ended up without insurance to pay the close to $2000 worth of medications he needed each month. Being a crusty Vermont soul, he decided the only thing he could do was go cold turkey. (Do not try this yourself!) Bob was lucky, despite significant withdrawal symptoms and a 911 call that resulted in a recommendation to be hospitalized, he persevered and to everyone’s amazement got radically better in all areas.

Bob Hit The Rewind Button and Look What Happened

Within 6 months, Bob was no longer diabetic. He had lost 3o pounds. His feet no longer swelled so he had no need of the water pill. He no longer needed meds for COPD because his pulse ox stayed in the mid to high 90’s.

Most significantly his pain was now only 3 out of 10 and controlled by over the counter Advil.

This is an example of hyperalgesia. Bob’s pain was being made worse on opioids and causing a host of other downstream issues. I realize that this is anecdotal but I share this story a lot because most people have never heard of anyone getting off their medications and showing improvement in a number of conditions that most people think of as chronic.

If you are facing knee replacement surgery and are currently on opioids, think twice about proceeding without first investigating whether the pain pills themselves may be causing increased pain sensitivity. Create a plan with your doctor.

If you are opioid naïve going into surgery, use them wisely for the purpose of gaining your range of motion back and feeling tolerable in the first two weeks. Sparing opioid use with attempts to gut it out will result in a longer knee replacement recovery and overall longer use of the pain medicines.

Resources

[1] Menendez ME, Ring D, Bateman BT. Preoperative opioid misuse is associated with increased morbidity and mortality after elective orthopaedic surgery. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2015 ;473(7):2402–12. Epub 2015 Feb 19

[2] Zywiel MG, Stroh DA, Lee SY, Bonutti PM, Mont MA. Chronic opioid use prior to total knee arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2011 ;93(21):1988–93.

[3] Namba RS, Inacio MCS, Pratt NL, Graves SE, Roughead EE, Paxton EW. Persistent opioid use following total knee arthroplasty: a signal for close surveillance. J Arthroplasty. 2018 ;33(2):331–6. Epub 2017 Sep 13.

[4] Bedard NA, Pugely AJ, Westermann RW, Duchman KR, Glass NA, Callaghan JJ. Opioid use after total knee arthroplasty: trends and risk factors for prolonged use. J Arthroplasty. 2017 ;32(8):2390–4. Epub 2017 Mar 16.

[5] Rozell JC, Courtney PM, Dattilo JR, Wu CH, Lee GC. Preoperative opiate use independently predicts narcotic consumption and complications after total joint arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2017 ;32(9):2658–62. Epub 2017 Apr 12.

[6] Cancienne JM, Patel KJ, Browne JA, Werner BC. Narcotic use and total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2018 ;33(1):113–8. Epub 2017 Aug 17.

[7] Goesling J, Moser SE, Zaidi B, Hassett AL, Hilliard P, Hallstrom B, Clauw DJ, Brummett CM. Trends and predictors of opioid use after total knee and total hip arthroplasty. Pain. 2016 ;157(6):1259–65.

[8] Weick, J, Bawa, H, Dirschl, D, Luu,H. Preoperative Opioid Use Is Associated with Higher Readmission and Revision Rates In Total Knee and Total Hip Arthroplasty The Journal of Bone & Joint Surgery. 2018;100(14):1171-1176.

[9] Trang T, Al-Hasani R, Salvemini D, Salter MW, Gutstein H, Cahill CM. Pain and Poppies: The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly of Opioid Analgesics. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2015;35(41):13879-13888. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2711-15.2015.